Short introduction by Fursat

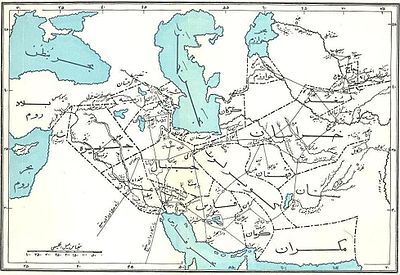

Fursat traces the territory of Âsâr-i ‘Ajam through a series of conceptual and geographical delimitations that identify the object of the book, extracting it from larger regions and topics. The book opens describing Iran as “a vast country whose places had many names that changed over time and comprised Irâq, Khurn, Tabarin, Frs, Azerban and Krmn and so on, places we are not concerned with” (Fursat 1896: 10). It outlines the region of Fars, naming its borders, its dimensions, its two climatic zones and its mayor cities: “Fars comprises (ibârat ast az) Shîrâz, Kâzirûn, Fîrûzabâd,

Dârbjird, Fâsâ, Nîrîz, Sarvistân, Kavar, Jahrum, Marvdasht, Shabankara and so on, and I do not plan to mention all of them” (Fursat 1896: 10).

Pars

In articulating this geographical and conceptual selection, Fursat moves between two different temporalities: the present in which he writes and travels through the ruins and the past of an “ancient epoch” (dar qadîm al-ayyâm). Fursat presents views that combine genealogy and etymology to explain this distant past.

Lands acquire names from their rulers, and the descendants inherit portions of the land, which are named after them.

Sometimes he endorses these views: Iran is named after Hûshang; his son Pars inherited it and so the whole of Iran was called Pars for a time. And Pars had several children named Jam, Shîrâz, Istakhr, Fâsâ after whom cities were named. Often, however, Fursat takes distance from this approach. The etymological past forms the foil against which Âsâr-i ‘Ajam constructs the ruins as an object of knowledge for the present. The past of origins and hearsay is contrasted with the evidence provided by drawings and descriptions that make up the book.

Iran and Islam

Fursat is less concerned with establishing a frame for the interpretation and evaluation of the past than with finding ways to come to terms with novel and singular objects of inquiry. This approach results in discussions of concrete ruins that appear foreign and unknown, rather than already mapped within a scheme of the relationship between the pre-Islamic past and Islam.

At the same time, as a counterpoint to this open inquiry, several passages of the book make it clear that the Âsâr-i ‘Ajam, the ruins of the non-Arabic speaking territory, are distant and far from the present day of Iran as a Muslim country.

At the beginning of the book the invocation to God is followed by one to Muhammad who is described as the one who “extinguished the fires of the Âtashkada’s of the Parsis and destroyed the religion of the Zoroastrians” (Fursat 1896: 2).

This invocation, written mostly with “Parsi” words, institutes a clear-cut break between the Zoroastrian past and the Muslim present. By establishing a fracture, the invocation authorizes a discussion of the ancients.The ancient past is approachable, not as an alternative to the order of things but as a different place whose traces dot the mountains and plains of the country. These traces elicit curiosity and should be studied scientifically.