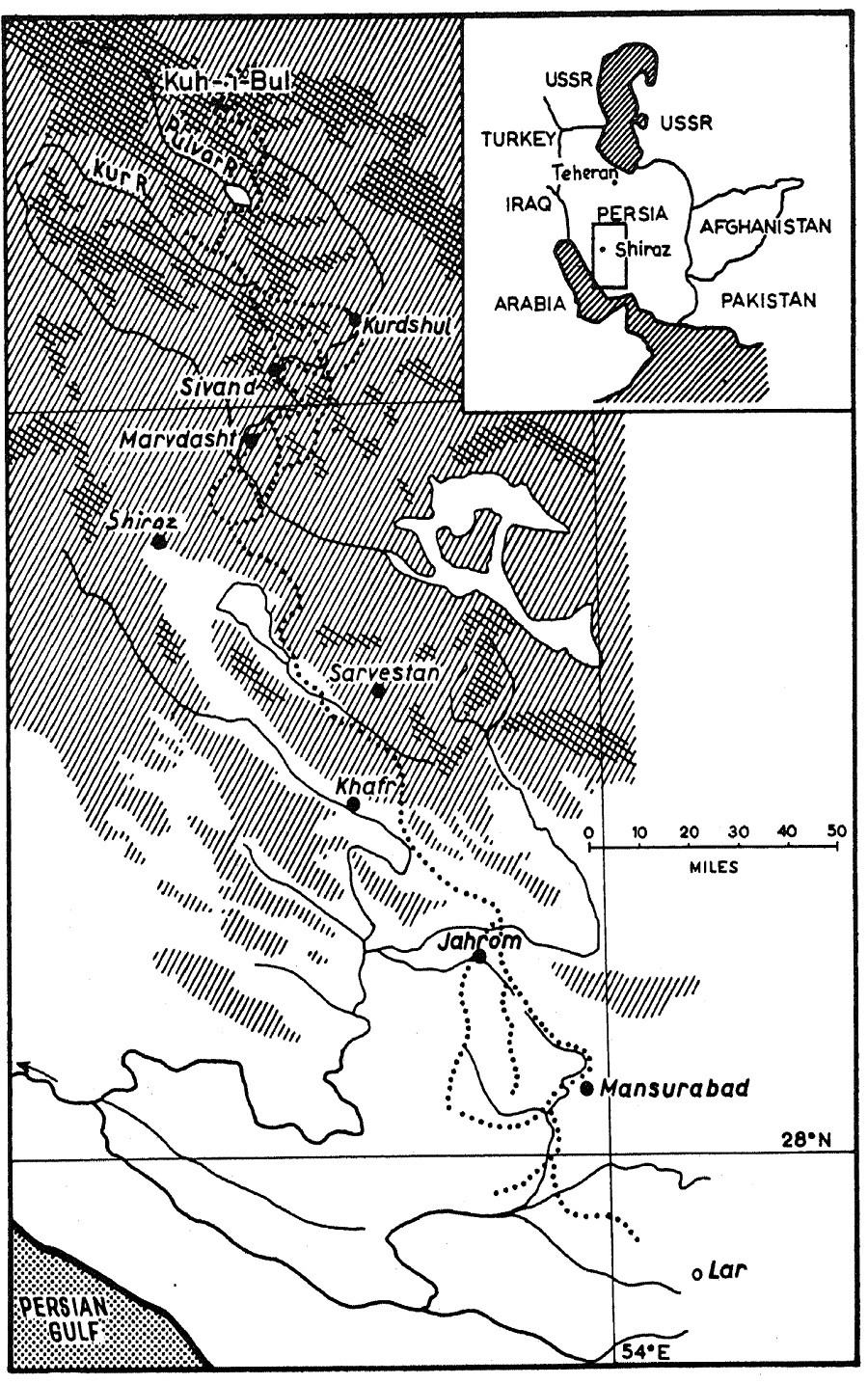

The Basseri are a tribe of tent-dwelling pastoral nomads who migrate in the arid steppes and mountains south, east and north of Shiraz in Fars province, South Persia. The area which they customarily inhabit is a strip of land, approximately 300 miles long and 20-50 miles wide, running in a fairly straight north-south line from the slopes of the mountain of Kuh-i-Bul to the coastal hills west of Lar. In this strip the tribe travels fairly compactly and according to a set schedule, so the main body of the population is at no time dispersed over more than a fraction of the route ; perhaps something like a 50-mile stretch, or 2,000 square miles.

Fars Province is an area of great ethnic complexity and admixture, and tribal units are best defined by political, rather than ethnic or geographical criteria. In these terms the Basseri are a clearly delim ited group, recognizing the authority of one supreme chief, and treated as a unit for administrative purposes by the Iranian authorities. The Basseri have furthermore in recent history been associated with some other tribes in the larger Khamseh confederacy; but this grouping has today lost most of its political and social meaning.

The total population of the Basseri probably fluctuates between 2,000 and 3,000 tents, depending on the changing fortunes of their chiefs as political leaders, and on the circumstances of South Persian nomadism in general. Today it is estimated at nearly 3,000 tents, or roughly 16,000 inhabitants.

The Basseri tribe is Persian-speaking, using a dialect very close to the urban Persian of Shiraz town; and most tribesmen know only that language, while some are bilingual in Persian and Turkish anda few in Persian and Arabic. All these three language communities are represented among their neighbours. Adjoining them in most of their route is the smaller Kurdshuli tribe, speaking the Luri dialect of Persian and politically connected with the Qashqai confederacy. Politically dependent on the Basseri are the remnants of the Turkish speaking Nafar tribe. The territories to the east are mostly occupied by various Arab tribes, some still Arabic-speaking and some Persian of the same dialect as the Basseri. Other adjoining areas to the east are dominated by the now largely sedentary Baharlu Turkish speaking tribe. All these eastern tribes were associated with the Basseri in the Khamseh confederacy. The opposing Qashqai confederacy domi nates the territories adjoining the Basseri on the west, represented by various branches of which the Shishbeluki are among the most important. These tribes are Turkish-speaking.

In addition to the Basseri population proper, various other groups are found that regard themselves as directly derived from the Basseri, while other groups claim a common or collateral ancestry. In most of the villages of the regions through which the Basseri migrate, and in many other villages and towns of the province, including Shiraz, is a considerable sedentary population of Basseri origin. Some of these are recent settlers many from the time of Reza Shah’s enforced settlement in the 30’s and some even later while others are third or fourth generation. In some of the villages of the north, notably in the Chahardonge area, the whole population regards itself as a settled section of the tribe, while in other places the settlers are dispersed as individuals or in small family groups.

Several other nomad groups also recognize a genetic connection with the Basseri, In the Isfahan area, mostly under the rule of the Dareshuri Turkish chiefs, are a number of Basseri who defected from the main body about 100 years ago and now winter in the Yazd-Isfahan plain and spend the summer near Semirun (Yazd-e-Khast). In north-west Fars a tribe generally known as the Bugard-Basseri migrates in a tract of land along the Qashqai-Boir Ahmed border. Finally, on the desert fringe east of Teheran, around Semnan, there is reported a considerable tribal population calling themselves Basseri, who are known and recognized as a collateral group by the Basseri of Fars.

The sparse historical traditions of the tribe are mainly connected with sectional history (pp. 52 ff.), or with the political and heroic exploits of recent chiefs (pp. 72 ff.). Of the tribe as a whole little is recounted., beyond the assertion that the Basseri have always occupied their present lands and were created from its dust assertions con tradicted by the particular traditions of the various sections.

Early Western travellers prove poor sources on the nomad tribes of Persia; but at least tribal names and sections are frequently given. The Basseri are variously described as Arab and Persian, as largely settled and completely nomadic. An early reference to them is found in Morier (1837: 232), based on materials collected in 1814-15. One would guess from the paucity of information on the tribe that it was relatively small and unimportant; overlordship over the tribe had, according to Persian historical compilations, been entrusted to the Arab chiefs in Safavid times (Lambton 1953: 159). According to the Ghavams, leaders of the Khamseh, the confederacy was formed about 90-100 years ago by the FaFaFa of the present Ghavam. In the beginning the Turk tribes of Baharlu and Aynarlu were predominant among the Khamseh, and the Basseri grew in importance only later. Most Basseri agree that the tribe has experienced a considerable growth in numbers and power during the last three generations.

During the enforced settlement in the reign of Reza Shah only a small fraction of the Basseri were able to continue their nomadic habit, and most were sedentary for some years, suffering a considerable loss of flocks and people. On Reza Shah’s abdication in 1941 migratory life was resumed by most of the tribesmen. The sections and camp-groups of the tribe were re-formed and the Basseri experienced a considerable period of revival. At present, however, the nomads are under external pressure to become sedentary, and the nomad population is doubtless on the decline.

The habitat of the Basseri tribe lies in the hot and arid zone around latitude 30 N bordering on the Persian Gulf. It spans a considerable ecologic range from south to north, ranging from low-lying salty and torrid deserts around Lar at elevations of 2,000 to 3,000 ft. to high mountains in the north, culminating in the Kuh-i-Bul at 13,000 ft. Precipitation is uniformly low, around 10″, but falls mainly in the winter and then as snow in the higher regions, so a considerable amount is conserved for the shorter growing season in that area. This permits considerable vegetation and occasional stands of forest to develop in the mountains. In the southern lowlands, on the other hand, very rapid run-off and a complete summer drought limits vegetation, apart from the hardiest desert scrubs, to a temporary grass cover in the rainy season of winter and early spring.

Agriculture offers the main subsistence of the population in the area, though not of the Basseri. It is under these conditions almost completely dependent on artificial irrigation. Water is drawn by channels from natural rivers and streams in the area, or, by the help of various contraptions, raised by animal traction from wells, particularly by oxen and horses. Finally, complex nets of qanats are constructed series of wells connected by subterranean aqueducts, whereby the groundwater of higher areas is brought out to the surface in lower parts of the valleys.

The cultivated areas, and settled populations, are found mostly in the middle zone around the elevation of Shiraz (5,000 ft. altitude), and also, somewhat more sparsely, as more or less artificial oases in the south. Settlement in the highest zones of the north is most recent, and still very sparse.

The pastoral economy of the Basseri depends on the utilization of extensive pastures. These pastures are markedly seasonal in their occurrence. In the strip of land utilized by the Basseri different areas succeed each other in providing the necessary grazing for the flocks. While snow covers the mountains in the north, extensive though rather poor pastures are available throughout the winter in the south. In spring the pastures are plentiful and good in the areas of low and middle altitude; but they progressively dry up, starting in early March in the far south. Usable pastures are found in the summer in areas above c. 6,000 ft; though the grasses may dry during the latter part of the summer, the animals can subsist on the withered straw, supplemented by various kinds of brush and thistles. The autumn season is generally poor throughout, but then the harvested fields with their stubble become available for pasturage. In fact most landowners encourage the nomads to graze their flocks on harvested and fallow fields, since the value of the natural manure is recognized.

The organization of the Basseri migrations, and the wider implications of this pattern, have been discussed elsewhere (Barth 1960). An understanding of the South Persian migration and land use pattern is facilitated by the native concept of the il-rah, the “tribal road”, Each of the major tribes of Fars has its traditional route which it travels in its seasonal migrations. It also has its traditional schedule of departures and duration of occupations of the different localities; and the combined route and schedule which describes the locations of the tribe at different times in the yearly cycle constitutes the il-rah of that tribe. Such an il-rah is regarded by the tribesmen as the property of their tribe, and their rights to pass on roads and over uncultivated lands, to draw water everywhere except from private wells, and to pasture their flocks outside the cultivated fields are recognized by the local population and the authorities. The route of an il-rah is determined by the available passes and routes of communication, and by the available pastures and water, while the schedule depends on the maturation of different pastures, and the movements of other tribes. It thus follows that the rights claimed to an il-rah do not imply exclusive rights to any locality throughout the year, and nothing prevents different tribes from utilizing the same localities at different times a situation that is normal in the area, rather than exceptional.

The Basseri il-rah extends in the south to the area of winter dispersal south of Jahrom and west of Lar. During the rainy season camps are pitched on the mountain flanks or on the ridges themselves to avoid excessive mud and occasional flooding. In early spring the tribes move down into the mainly uncultivated valleys of that region, and progressively congregate on the Benarou-Mansurabad plain. The main migration commences at the spring equinox, the time of the Persian New Year. The route passes close by the market town of Jahrom, and northward over a series of ridges and passes separating a succession of large flat valleys. The main bottleneck, both for reasons of natural communication routes and because of the extensive areas of cultivation, is the Marvdasht plain, where the ruins of Persepolis are located. Here the Basseri pass in the end of April and beginning of May, crossing the Kur river by the Pul-e-Khan or Band-Amir bridges, or by ferries. In the same period, various Arab and Qashqai tribes are also funnelled through this area.

Continuing northward, the Basseri separate and follow a number of alternative routes, some sections lingering to utilize the spring pastures in the adjoining higher mountain ranges, others making a detour to the east to pass through some villages recently acquired by the Basseri chief. The migration then continues into the uppermost Kur valley, where some sections remain, while most of the tribe pushes on to the Kuh-i-Bul area, where they arrive in June.

While camp is moved on most days during this migration, the population becomes more stationary in the summer, camping for longer periods and moving only locally. The first camps commence the return journey in the end of August, to spend some weeks in the Marvdasht valley grazing their flocks on the stubble and earning cash by labour; most go in the course of September. As the pastures are usually poor the tribe travels rapidly with few or no stops, and reaches the south in the course of 40 50 days, by the same route as the spring journey. During winter, as in the summer, migrations are local and short and camp is broken only infrequently.

The Basseri keep a variety of domesticated animals. Of far the greatest economic importance are sheep and goats, the products of which provide the main subsistence. Other domesticated animals are the donkey for transport and riding (mainly by women and children), the horse for riding only (predominantly by men), the camel for heavy transport and wool, and the dog as watchdog in camp. Poultry are sometimes kept as a source of meat, never for eggs. Cattle are lacking, reportedly because of the length of the Basseri migrations and the rocky nature of the terrain in some of the Basseri areas.

There are several common strains of sheep in Fars, of different productivity and resistance. Of these the nomad strain tends to be larger and more productive. But its resistance to extremes of temperature, particularly to frost, is less than that of the sheep found in the mountain villages, and its tolerance to heat and parched fodder and drought is less than that of the strains found in the south. It has thus been the experience of nomads who become sedentary, and of occasional sedentary buyers of nomad livestock, that 70-80 % of the animals die if they are kept throughout the year in the northern or southern areas. The migratory cycle is thus necessary to maintain the health of the nomads’ herds, quite apart from their requirements for pastures.

Sheep and goats are generally herded together, with flocks of up to 300-400 to one shepherd unassisted by dogs. About one ram is required for every five ewes to ensure maximal fertility in the flock, whereas in the case of goats the capacity of a single male appears to be much greater. The natural rutting seasons are three, falling roughly in June, August/September, and October; and the ewes consequently throw their lambs in November, January/February, or March. Some sections of the tribe (e. g. the Il-e-Khas) who winter further north in the zone of middle altitude separate the rams and the ewes in the August/September rutting period to prevent early lambing.

Lambs and kids are usually herded separately from the adults, and those born during the long migrations are transported strapped on top of the nomads’ belongings on donkeys and camels for the first couple of weeks. A simple device to prevent suckling, a small stick through the lamb’s mouth which presses down the tongue and is held in place by strings leading back behind the head, is used to protect the milk of the ewes when lambs and kids travel with the main herd. Earl) weaning is achieved by placing the lamb temporarily in a different flock from that of its mother.

The animals have a high rate of fertility, with moderately frequent twinning and occasionally two births a year. However, the herds are also subject to irregular losses by disaster and pest; mainly heavy frosts at the time of lambing, and foot-and-mouth disease and other contagious animal diseases. In bad years, the herds may, suffer average losses of as much as 50 %. Contrary to general reports, the main migrations are not in themselves the cause of particular losses of livestock, by accident or otherwise.

The products derived from sheep -and goats are milk, meat, wool and hides, while of the camel only the wool is used. These products are variously obtained and processed, and are consumed directly, stored and consumed, or traded.

Milk and its products are most important. Sheep’s and goats’ milk are mixed during milking. Milk is never consumed fresh, but immediately heated slightly above body temperature, and started off by a spoonful of sour milk or the stomach extract of a lamb; it then rapidly turns into sour milk or junket respectively. Cheese is made from the junket; it is frequently aged but may also be consumed fresh. Cheese production is rarely attempted in periods of daily migrations, and the best cheese is supposed to be made in the relatively stationary period of summer residence.

Sour milk (mast) is a staple food, and particularly in the period of maximal production in the spring it is also processed for storage. By simple pressing in a gauze-like bag the curds may be separated from the sour whey; these curds are then rolled into walnut-sized balls and dried in the sun (kashk) for storage till winter. The whey is usually discarded or fed to the dogs; the Il-e-Khas are unusual, and frequently ridiculed, for saving it and producing by evaporation a solid residue called qara ghorut, analogous to Scandinavian “goat cheese”.

Sour milk may also be churned, or actually rocked, in a goat skin (mashk) suspended from a tripod, to produce butter and buttermilk (dogh). The latter is drunk directly, the former is eaten fresh, or clarified and stored for later consumption or for sale.

Most male and many female lambs and kids are slaughtered for meat; this is eaten fresh and never smoked, salted or dried. The hides of slaughtered animals are valuable; lambskins bring a fair price at market, and the hides of adults are plucked and turned inside out, and used as storage bags for water, sour milk and buttermilk. The skins of kids, being without commercial value and rather small and weak, are utilized as containers for butter etc.

Wool is the third animal product of importance. Lamb’s wool is made into felt, and sheep’s wool and camel-hair are sold, or spun and used in weaving and rope-making. Goat-hair is spun and woven.

In the further processing of some of these raw products, certain skills and crafts are required. Though the nomads depend to a remarkable extent on the work of craftsmen in the towns, and on industrial products, they are also dependent on their own devices in the production of some essential forms of equipment.

Most important among these crafts are spinning and weaving. All locally used wool and hair is spun by hand on spindlewhorls of their own or Gypsy (cf. pp. 91-93) production an activity which consumes a great amount of the leisure time of women. All saddlebags, packbags and sacks used in packing the belongings of the nomads are woven by the women from this thread, as are the rugs used for sleeping. Carpets are also tied, as are the outer surfaces of the finest pack and saddle-bags. Furthermore, the characteristic black tents consist of square tentcloths of woven goat-hair this cloth has remarkable water-repellent and heat-retaining properties when moist, while when it is dry, i.e. in the summer season, it insulates against radiation heat and permits free circulation of air. All weaving and carpet-tying is done on a horizontal loom, the simplest with merely a movable pole to change the sheds. None of these often very attractive articles are produced by the Basseri for sale.

Otherwise, simple utilitarian objects of wood such as tent poles and pegs, wooden hooks and loops bent over heat, and camels’ pack saddles are produced by the nomads themselves. Ropes for the tents, and for securing pack loads and hobbling animals are twined with 3-8 strands. Some of the broader bands for securing loads are woven. Finally, various repairs on leather articles, such as the horses’ bridles, are performed by the nomads, though there is no actual production of articles of tanned leather. Clothes for women are largely sewn by the women from bought materials, while male clothes are bought ready made.

Hunting and collecting are of little importance in the economy, though hunting of large game such as gazelle and mountain goat and sheep is the favourite sport of some of the men. In spring the women collect thistle-sprouts and certain other plants for salads or as vegetables, and at times are also able to locate colonies of truffles, which are boiled and eaten.

The normal diet of the Basseri includes a great bulk of agricultural produce, of which some tribesmen produce at least a part themselves. Cereal crops, particularly wheat, are planted on first arrival in the summer camp areas, and yield their produce before the time of departure ; or locally resident villagers are paid to plant a crop before the nomads arrive, to be harvested by the latter. The agriculture which the nomads themselves perform is quite rough and highly eclectic; informants agreed that the practice is a recent trend of the last 10-15 years. Agricultural work in general is disliked and looked down upon, and most nomads hesitate to do any at all. The more fortunate, however, may own a bit of land somewhere along the migration route, most frequently in northern or southern areas, which they as landlords let out to villagers on tenancy contracts, and from which they may receive from 1/6 to 1/2 of the gross crop. Such absentee “landlords” do no agricultural work themselves, nor do they usually provide equipment or seed to their tenants.

A great number of the necessities of life are thus obtained by trade. Flour is the most important foodstuff, consumed as unleavened bread with every meal; and sugar, tea, dates, and fruits and vegetables are also important. In the case of most Basseri, such products are entirely or predominantly obtained by trade. Materials for ‘clothes, finished clothes and shoes, all glass, china and metal articles including all cooking utensils, and saddles and thongs are also purchased, as well as narcotics and countless luxury goods from jewelry to travelling radios. In return, the products brought to market are almost exclusively clarified butter, wool, lambskins, and occasional live stock.